| Type |

V4 Single seat fighter |

A-0 (D) Single seat fighter |

V8 Record |

| Engine |

1 Daimler-Benz DB 601 A |

1 Daimler-Benz DB 601 M |

1 Daimler-Benz DB 601 R |

| Dimensions |

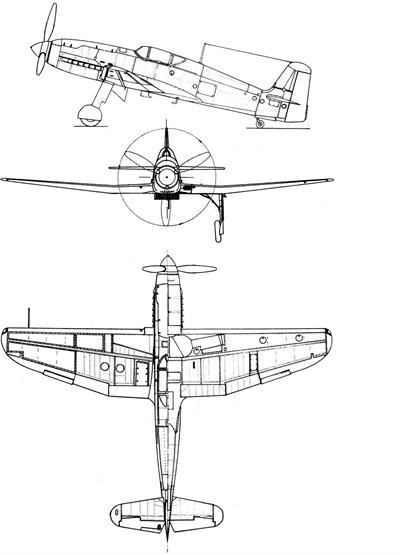

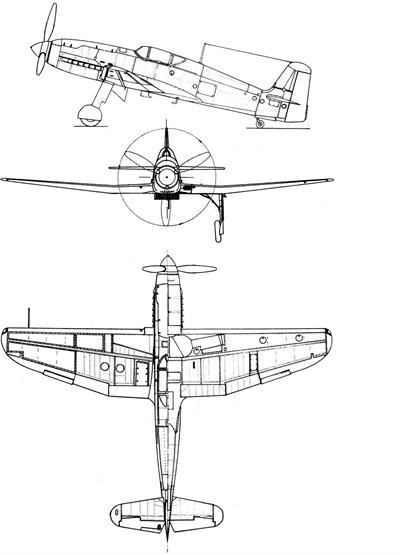

Length 8,20 m , height 3,60 m, span 9,42 m , wing area 14,50 m2 , |

Length 8,20 m , height 3,60 m, span 9,40 m , wing area 14,60 m2 |

Length 8,18 m , height 3,60 m, span 7,60 m , wing area 11,00 m2 |

| Weights |

Empty 2097 kg, loaded 2540 kg, max. take off weight |

Empty 2010 kg, loaded 2500 kg, max. take off weight |

Empty 1865 kg, loaded 2475 kg, max. take off weight |

| Performance |

Max.. speed 670 km/h at 5000 m,560 km/h at sea level cruising speed 555 km/h at 2000 m, landing speed 150 km/h , range 1050 km, endurance , service ceiling 11000 m, climb to 2000 m 2,0 min., to 4000 m 4,0 min., to 6000 m 6,5 min., to 8000 m 10,5 min., |

Max.. speed 670 km/h at 5000 m,575 km/h at sea level cruising speed 550 km/h at 2000 m, landing speed 150 km/h , range 1000 km, endurance , service ceiling 11000 m, climb to 2000 m 2,2 min., to 4000 m 5,0 min., to 6000 m 7,8 min. |

Max.. speed 770 km/h |

| Armament |

None |

2 7,92 mm MG 17 , 1 20 mm MG/FF or 2 15 mm MG 151 |

None |

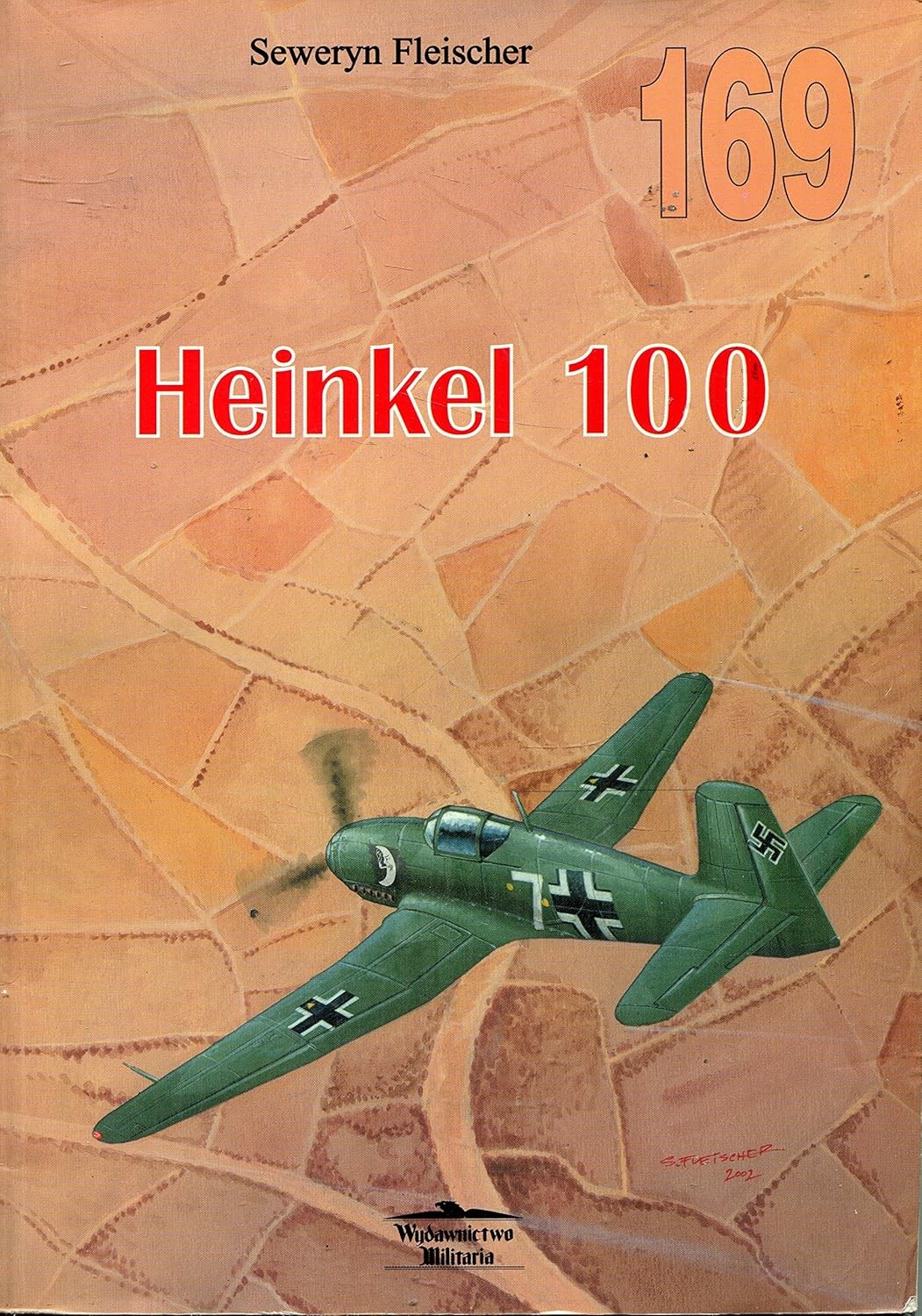

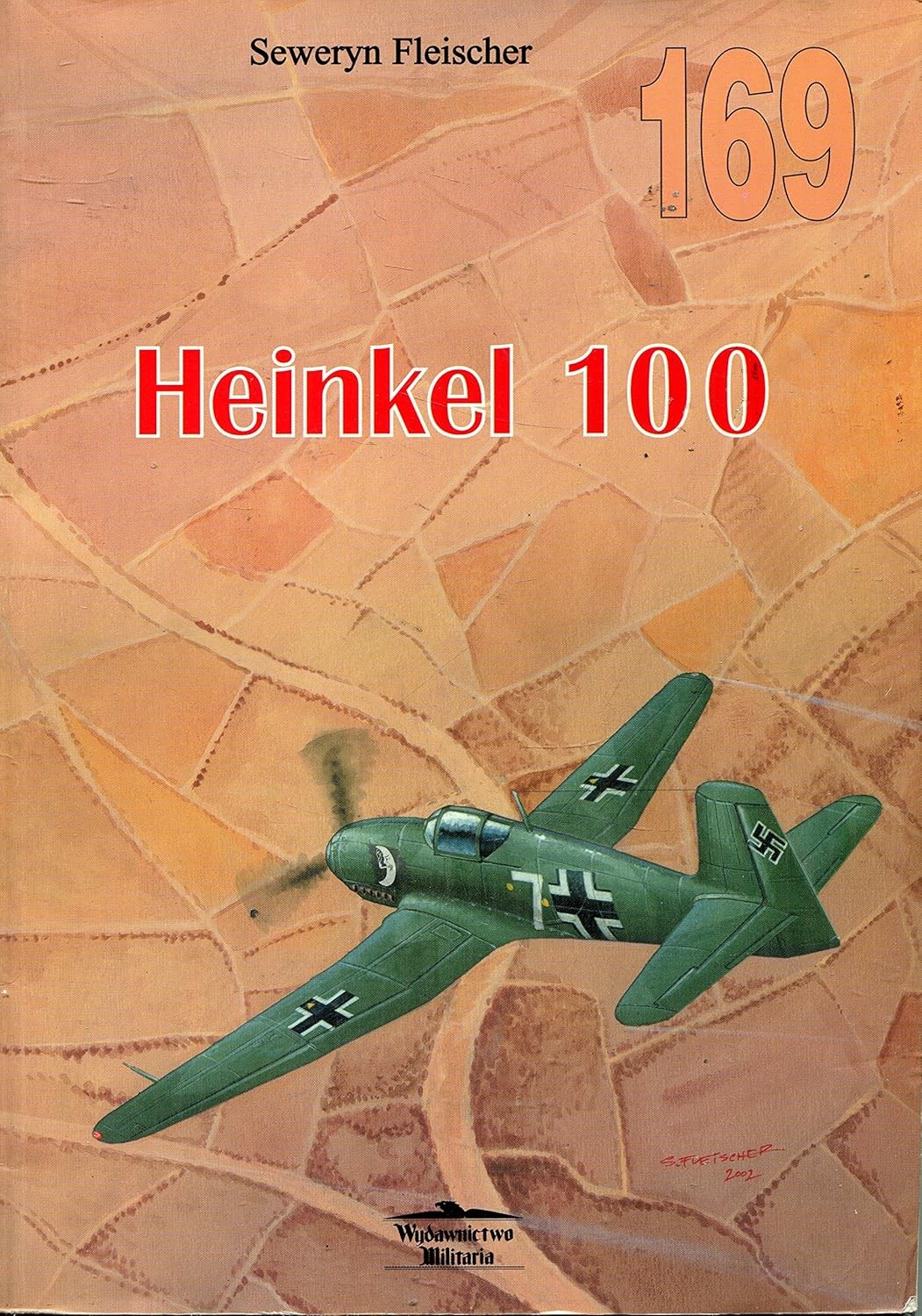

There is a debate regarding the correct designation of the He 100 aircraft actually built. Green (1970) cited "A", "B", "C" and "D" variants, and that later He 100 prototypes and all pre-production He 100s were called "He 100D-0" and "He 100D-1" production runs. However, Heinkel documents indicate that the pre-production were only designated He 100A-0, and that all of the He 100s built were essentially the same, with even the prototypes later updated to the production standard before they were exported to the Soviet Union. Thus, supposed "He 100B", "He 100C", and "He 100D" designations are fictitious postwar inventions.

There is a debate regarding the correct designation of the He 100 aircraft actually built. Green (1970) cited "A", "B", "C" and "D" variants, and that later He 100 prototypes and all pre-production He 100s were called "He 100D-0" and "He 100D-1" production runs. However, Heinkel documents indicate that the pre-production were only designated He 100A-0, and that all of the He 100s built were essentially the same, with even the prototypes later updated to the production standard before they were exported to the Soviet Union. Thus, supposed "He 100B", "He 100C", and "He 100D" designations are fictitious postwar inventions.Following the selection by the RLM of the Bf 109 as its next single-seat fighter over the He 112, Ernst Heinkel became interested in a new fighter that would surpass the performance of the Bf 109 as much as the Bf 109 had surpassed that of the biplanes it replaced.[1] Other German designers had similar ambitions, including Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf. There was never an official project on the part of the RLM, but Rudolf Lucht felt that new designs were important enough to fund the projects from both companies to provide "super-pursuit" designs for evaluation. This would result in the single-engined He 100 fighter, and the promising twin-engine Fw 187 Falke Zerstörer-style heavy fighter, both reaching the flight stage of development.

Walter Günter, one half of the famous Günter brothers, looked at the existing He 112, which had already been heavily revised into the He 112B version, and decided it had reached the end of its development and started a completely new design, Projekt 1035. Learning from past mistakes on the 112 project, the design was to be as easy to build as possible yet 700 km/h was a design goal. To ease production, the new design had considerably fewer parts than the 112 and those that remained contained fewer compound curves.In comparison, the 112 had 2,885 parts and 26,864 rivets, while the P.1035 was made of 969 unique parts with 11,543 rivets. The new straight-edged wing was a source of much of the savings; after building the first wings, Otto Butter reported that the reduction in complexity and rivet count (along with the Butter brothers' own explosive rivet system) saved an astonishing 1,150 man hours per wing.

The super-pursuit type was not a secret, but Ernst Heinkel preferred to work in private and publicly display his products only after they were developed sufficiently to make a stunning first impression.[citation needed] As an example of this, the mock-up for the extremely modern-looking He 100 was the subject of company Memo No.3657 on 31 January that stated: "The mock-up is to be completed by us ... as of the beginning of May ... and be ready to present to the RLM ... and prior to that no one at the RLM is to know of the existence of the mock-up."

Walter Günter was killed in a car accident on 25 May 1937, and design work was taken over by his twin brother Siegfried, who finished the final draft of the design later that year. Heinrich Hertel, a specialist in aircraft structures, also played a prominent role in the design. At the end of October the design was submitted to the RLM, complete with details on prototypes, delivery dates and prices for three aircraft delivered to the Rechlin test center.

The He 100 should have been designated He 113, but since the number "13" was unlucky, it was not used. It is reported that Ernst Heinkel lobbied for this "round" number in the hope that it would improve the design's chances for production.

In order to get the promised performance the design included a number of drag-reducing features,. The landing gear (including the tailwheel) was retractable and completely enclosed in flight.

There was also a serious shortage of advanced aero engines in Germany during the late 1930s. The He 100 used the same Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine as the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Bf 110, and there was insufficient capacity to support another aircraft using the same engine. The only available alternative engine was the Junkers Jumo 211, and Heinkel was encouraged to consider its use in the He 100. However, the early Jumo 211 then available did not use a pressurized cooling system, and it was therefore not suitable for the He 100's evaporative cooling system. Furthermore, a Jumo 211-powered He 100 would not have been able to outperform the contemporary DB 601-powered Bf 109 because the supercharger on the early Jumo 211 was not fully shrouded. In order to reduce weight and frontal area, the engine was mounted directly to the forward fuselage, which was strengthened and literally tailored to the DB 601, as opposed to conventional mounting on engine bearers. The cowling was very tight-fitting, and as a result the aircraft has something of a slab-sided appearance.

In order to provide as much power as possible from the DB 601, exhaust ejectors were used to provide a small amount of additional thrust. The supercharger inlet was moved from the normal position on the side of the cowling to a location in the leading edge of the left wing. Although cleaner-looking, the long, curved induction pipe most probably negated any benefit.

For the rest of the designed performance increase with the DB 601 powerplant, Walter turned to the experimental method of evaporative cooling. Heinkel and the Günter brothers were avid proponents of the technology, and had previously used it on the He 119, with promising results. Evaporative or "steam" cooling promised a completely drag-free cooling system and reduced weight. No detailed plans of the installation survive. The earlier prototypes varied, but they were all eventually modified to something close to the final standard before they were exported to the Soviet Union.

The first prototype He 100 V1 flew on 22 January 1938, only a week after its promised delivery date. The aircraft proved to be outstandingly fast. However, it continued to share a number of problems with the earlier He 112, notably a lack of directional stability. In addition, the Luftwaffe test pilots disliked the high wing loading, which resulted in landing speeds so great that they often had to use brakes right up to the last 100 m of the runway. The ground crews also disliked the design, complaining about the tight cowling which made servicing the engine difficult. But the big problem turned out to be the cooling system, largely to no one's surprise. After a series of test flights V1 was sent to Rechlin in March.

The second prototype He 100 V2 addressed the stability problems by changing the vertical stabilizer from a triangular form to a larger and more rectangular form. The oil-cooling system continued to be problematic, so it was removed and replaced with a small semi retractable radiator below the wing. It also received the still-experimental DB 601M engine which the aircraft was originally designed for. The M version was modified to run on "C3" fuel at 100 octane, which would allow it to run at higher power ratings in the future.

V2 was completed in March, but instead of moving to Rechlin it was kept at the factory for an attempt on the 100 km (62 mi) closed circuit speed record. A course was marked out on the Baltic coast between Wustrow and Müritz, 50 km apart, and the attempt was to be made at the aircraft's best altitude of 5,500 m . After some time cleaning out the bugs the record attempt was set to be flown by Captain Herting, who had previously flown the aircraft several times.

At this point Ernst Udet showed up and asked to fly V2, after pointing out he had flown the V1 at Rechlin. He took over from Herting and flew the V2 to a new world 100 km closed-circuit record on 5 June 1938, at 634.73 km/h . Several of the cooling pumps failed on this flight as well, but Udet wasn't sure what the lights meant and simply ignored them.

The record was heavily publicized, but in the press the aircraft was referred to as the "He 112U". Apparently, the "U" stood for "Udet". At the time the 112 was still in production and looking for customers, so this was one way to boost sales of the older design. V2 was then moved to Rechlin for continued testing. Later in October, the aircraft was damaged on landing when the tail wheel didn't extend, and it is unclear if the damage was repaired.

The V3 prototype received the clipped racing wings, which reduced span and area from 9.40 m and 14.4 square metres , to 7.59 m and 11 m2 . The canopy was replaced with a much smaller and more rounded version, and all of the bumps and joints were puttied over and sanded down. The aircraft was equipped with the 601M and flown at the factory.

In August, the DB 601R engine arrived from Daimler-Benz and was installed. This version increased the maximum rpm from 2,200 to 3,000, and added methyl alcohol to the fuel mixture to improve cooling in the supercharger and thus increase boost. As a result, the output was boosted to 1,800 PS; 1,776 hp (1,324 kW), although it required constant maintenance and the fuel had to be drained completely after every flight. The aircraft was then moved to Warnemünde for the record attempt in September.

On one of the pre-record test flights by the Heinkel chief pilot, Gerhard Nitschke, the main gear failed to extend and ended up stuck half open. Since the aircraft could not be safely landed it was decided to have Nitschke bail out and let the aircraft crash in a safe spot on the airfield. Gerhard was injured when he hit the tail on the way out, and made no further record attempts.

V4 was to have been the only "production" prototype and was referred to as the "100B" model (V1 through V3 being "A" models). It was completed in the summer and delivered to Rechlin, so it wasn't available for modification into racing trim when V3 crashed. Although the aircraft was unarmed it was otherwise a service model with the 601M, and in testing over the summer it proved to be considerably faster than the Bf 109. At sea level, the aircraft could reach 560 km/h , faster than the Bf 109E's speed at its best altitude. At 2,000 m , it improved to 610 km/h , topping out at 669 km/h at 5,000 m before falling again to 641 km/h at 8,000 m . The aircraft had flown a number of times before its landing gear collapsed while standing on the pad on 22 October. The aircraft was later rebuilt and was flying by March 1939.

Although V4 was to have been the last of the prototypes in the original plans, production was allowed to continue with a new series of six aircraft. One of the airframes was selected to replace V3, and as luck would have it V8 was at the "right point" in its construction and was completed out of turn. It first flew on 1 December but this was with a standard DB 601Aa engine. The 601R was then put in the aircraft on 8 January 1939, and moved to a new course at Oranienberg. After several shakedown flights, Hans Dieterle flew to a new record on 30 March 1939, at 746.6 km/h . Once again the aircraft was referred to as the He 112U in the press. It is unclear what happened to V8 in the end; it may have been used for crash testing.

V5 was completed like V4, and first flew on 16 November. It was later used in a film about V8's record attempt, in order to protect the record breaking aircraft. At this point, a number of changes were made to the design resulting in the "100C" model, and with the exception of V8 the rest of the prototypes were all delivered as the C standard.

V6 was first flown in February 1939, and after some test flights at the factory it was flown to Rechlin on 25 April. There it spent most of its time as an engine testbed. On 9 June, the gear failed inflight, but the pilot managed to land the aircraft with little damage, and it was returned to flying condition in six days.

V7 was completed on 24 May with a change to the oil cooling system. It was the first to be delivered with armament, consisting of two 20 millimetres MG FF cannon in the wings and four 7.92 mm MG 17 machine guns arranged around the engine cowling. This made the He 100 the most heavily armed fighter of its day. V7 was then flown to Rechlin where the armament was removed and the aircraft was used for a series of high speed test flights.

V9 was also completed and armed, but was used solely for crash testing and was "tested to destruction". V10 was originally to suffer a similar fate, but instead ended up being given the racing wings and canopy of the V8 and displayed in the German Museum in Munich as the record-setting "He 112U". It was later destroyed in a bombing attack.

Overheating problems and general failures with the cooling system motors continued to be a problem. Throughout the testing period, failures of the pumps ended flights early, although some of the test pilots simply started ignoring them. In March, Kleinemeyer wrote a memo to Ernst Heinkel about the continuing problems, stating that Schwärzler had asked to be put on the problem.

Another problem that was never cured during the prototype stage was a rash of landing gear problems. Although the wide-set gear should have eliminated the collapse of landing gears that plagued the Bf 109, especially in the difficult take-offs and landings, the He 100's landing gear was not built to withstand heavy use, and as a result they were no improvement over the Bf 109. V2, 3, 4 and 6 were all damaged to various degrees due to various gear failures, a full half of the prototypes.

He 100 D-0

Throughout the prototype period, the various models were given series designations (as noted above), and presented to the RLM as the basis for series production. The Luftwaffe never took Heinkel up on their offer although the company decided to build a total of 25 of the aircraft one way or the other, so with 10 down, there were another 15 of the latest model to go. In keeping with general practice, any series production is started with a limited run of "zero series", resulting in the He 100 D-0.

The D-0 was similar to the earlier C models, with a few notable changes. Primary among these was a larger vertical tail in order to finally solve the stability issues. In addition, the cockpit and canopy were slightly redesigned, with the pilot sitting high in a large canopy with excellent vision in all directions. The armament was reduced from the C model to one 20 mm MG FF/M in the engine V firing through the propeller spinner, and two 7.92 mm MG 17s in the wings close to the fuselage.

The three D-0 aircraft were completed by the summer of 1939 and stayed at the Heinkel Marienehe plant for testing. They were later sold to the Japanese Imperial Navy to serve as pattern aircraft for a production line, and were shipped there in 1940. They received the designation AXHe1.

He 100 D-1

The final evolution of the short He 100 history is the D-1 model. As the name suggests, the design was supposed to be very similar to the pre-production D-0s, the main planned change being to enlarge the horizontal stabilizer. The big change was the abandonment of the surface cooling system, which proved to be too complex and failure-prone. A larger version of the retractable radiator was installed, and this appeared to cure the problems. The radiator was inserted in a "plug" below the cockpit, widening the wings slightly.

Though the aircraft failed to match its design speed of 700 km/h once it was equipped with weapons, the larger canopy and the radiator, it was still capable of speeds in the 644 km/h range. The He 100 had a combat range of 900 to 1,000 km compared to 600 km for the Bf 109 by virtue of its low drag airframe. While not in the same league as the later escort fighters, this was at the time a superb range, which could mean that a production Heinkel 100 might have offset the need for the Bf 110.

Since by this point, however, the war was under way, and as the Luftwaffe would not purchase the aircraft in its current form, the production line was shut down. There were allegations that politics played a role in stopping production of the He 100 the remaining 12 He 100 D-1 fighters were used to form Heinkel's Marienehe factory defense unit, flown by factory test pilots. They replaced the earlier He 112s that were used for the same purpose and the 112s were sold. Early in the war, there were no bombers venturing that far into Germany and it appears that the unit never saw action. The fate of the D-1s remains unknown. The aircraft were also used for a propaganda spoof, as the supposed Heinkel He 113.

Foreign use

When the war opened in 1939 Heinkel was allowed to look for foreign licensees for the design. Japanese and Soviet delegations visited the Marienehe factory on 30 October 1939 and were both impressed by the design. The Soviets were particularly interested in the surface cooling system, having built the experimental Ilyushin I-21 with evaporative cooling and to gain experience with it they purchased the six surviving prototypes (V1, V2, V4, V5, V6 and V7).After arriving in the USSR they were passed onto the TsAGI institute for study.

The Japanese were also looking for new designs, notably those using inline engines, where they had little experience and purchased the three D-0s for 1.2 million RM, as well as a license for production and a set of jigs for another 1.6 million RM. The three D-0s arrived in Japan in May 1940 and were re-assembled at Kasumigaura. They were then delivered to the Japanese Naval Air Force where they were renamed AXHe1, for "Experimental Heinkel Fighter". When referring to the German design, the aircraft is called both the He 100 and He 113, with at least one set of plans bearing the latter name.

The prototypes were accompanied by Heinkel test pilot Gerhard Nitschke, who worked with Lieutenant Mitsugi Kofukuda during the testing and evaluation. The Navy was so impressed by tests that they planned to put the aircraft into production as soon as possible, as their land-based interceptor. (Unlike every other armed forces organization in the world, the Japanese Army and Navy both fielded complete land-based air forces.) Hitachi won the contract for the aircraft and started construction of a factory in Chiba for its production. With the European war on, the jigs and plans never arrived.