THE RAID THAT NEVER WAS

By Ken Wakefield

IN the autumn of 1943, Adolf Hitler, frustrated by the inability of the Luftwaffe to retaliate for the heavy and sustained bombing of German cities, nominated Generalmajor Dietrich Peltz to the rank of Angriffsfuhrer England. In this capacity he was to reorganise and train the bomber force in the west, and then carry out a renewed offensive against Britain.

Peltz was well qualified for his new appointment and it is

doubtful if Hitler could have chosen an officer better suited

for the difficult task which lay ahead. Although young by usual

senior officer standards. Peltz was very experienced, both as

a bomber pilot and as a staff officer, and his rapid promotion

had been well earned. With customary zeal and efficiency

Peltz did everything possible to build up and train an

efficient bomber force. But his problems were many and diffi-

cult to resolve - among other things insufficient aircraft were

available, additional aircraft were slow to arrive, and many

of his crews were inexperienced and inadequately trained.

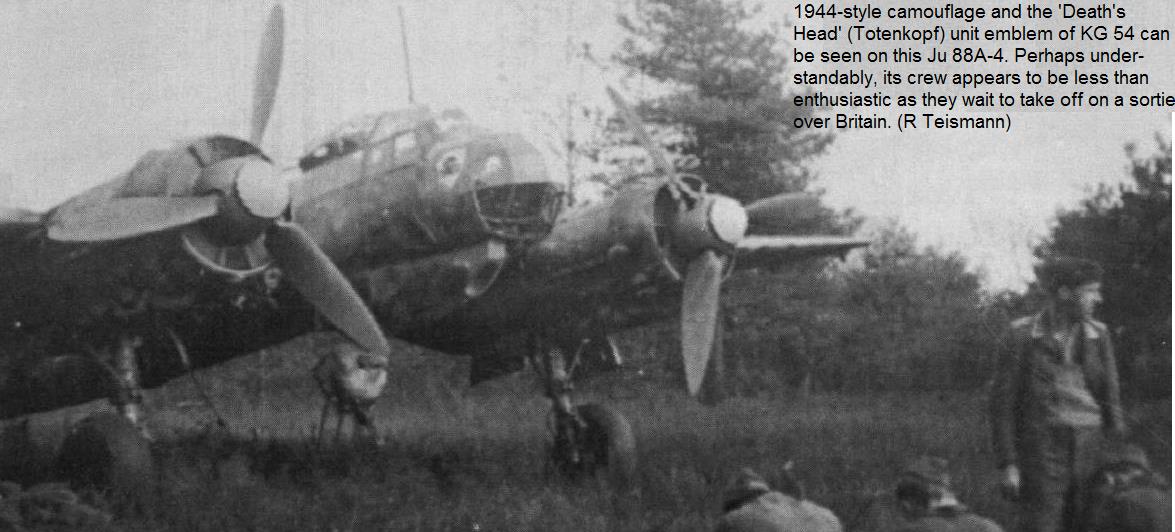

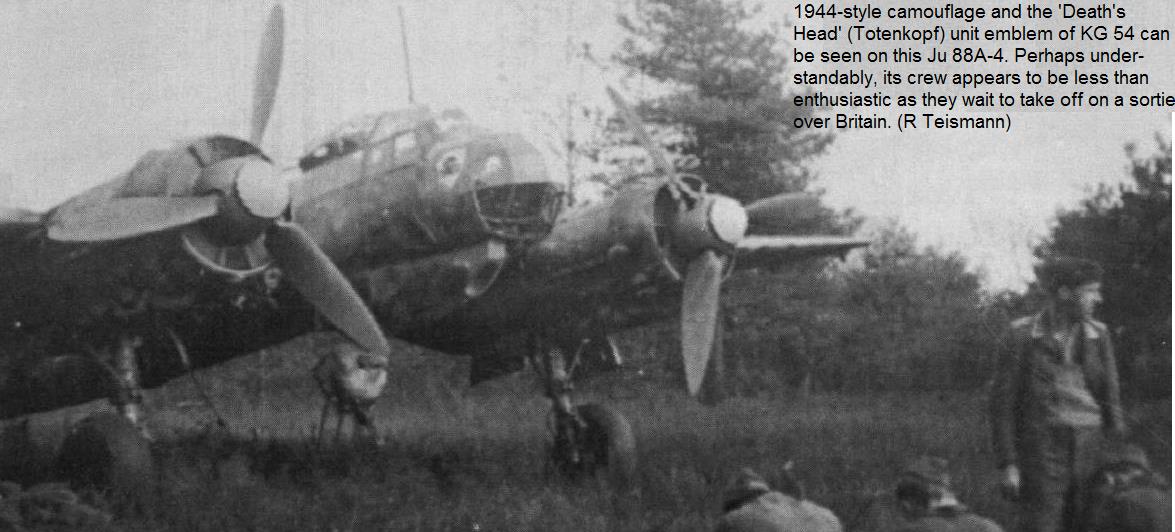

The types of aircraft under his command also left much to be

desired; by RAF standards none were capable of lifting a

heavy bomb load and although they included a small number

of He 177 heavy bombers, the majority were in the medium

category. They included some of the newest types, such as

the Ju 88S and late versions of the Ju 188 and Do 217. but

most were elderly Ju 88A-4s and slightly improved but

basically similar Ju 88A-14s.

The offensive was due to open towards the end of 1943.

but because of his problems Peltz was unable to launch a

major attack until the night of 21 January. 1944. The target

was London and by using all available crews and aircraft,

many flying double missions. Peltz was able to dispatch 447

sorties in a two phase attack. However, according to British

sources only 92 aircraft pene- trated inland, with 13 reaching

Greater London where 32 tons of bombs reportedly fell.

The attack could hardly be adjudged a success, and the loss of 21 aircraft was cause for concern. Replacements were slow to materialise and a loss rate of this nature could not be sus-

tained for long without seriously impairing the offensive. The actual number of bombers serviceable and available for operations on 20 January was 431 - made up of 74 Do 217s. 31 Ju

188s and 25 Me 410s of KG 2. 120 Ju 88s of KG 6. 31 Ju 88s of KG 30. 15 He 177s of KG 40. 61 Ju 88s of KG 54. 23 Do 217s of KG 66. four Ju 88s of KG 76. 27 He 177s of KG 100.

and 20 FW 190s of SKG 10 - and anything less than this total was considered insufficient. It was not an insignificant force, but its bomb carrying potential was a far cry from that of RAF

Bomber Command and the US Eighth Air Force. By comparison, at this stage of the war the British were regularly dispatching 800-900 four-engined heavy

bombers at night and the Americans about the same number or more by day.

The London attack on the night of 21 January was the heaviest experienced in Britain since July

1942 and. mainly for home consumption as a morale booster. German propaganda made much of it.

In reality, however, little damage was caused and casualties were few.

Another, rather more successful attack was made on London on 29 January, more followed over the

next few months and by the end of March the "Baby Blitz', as the offensive was known in Britain, had

produced 15 large scale attacks and 11 of a lesser nature. Most were directed against London and

although at times they caused much damage to private property and inflicted more suffering on an

already hard hit civilian population, they more often achieved little of note. On I March an attempted

attack on Hull was totally ineffective, but the following night the Luftwaffe returned to London where, as

on previous occasions, damage was mainly confined to residential and business premises. Nowhere,

from the outset, did damage greatlv affect the war effort and the attacks did nothing to stem pre-

parations for the forthcoming Allied invasion.

Unlike the Night Blitz of 1940-41 and. to a lesser degree, the Baedeker Raids of 1942. the night

defences now had the upper hand. Large numbers of radar controlled AA guns. *Z" rocket batteries

and search lights, together with a well equipped night fighter force directed by a superb Ground

Controlled Interception (GCI) radar system, took a heavy toll of the attackers whose troubles were

further compounded by an efficient radio countermeasures organisation.

Against such opposition it is not surprising that many attacks went astray, despite the efforts made by

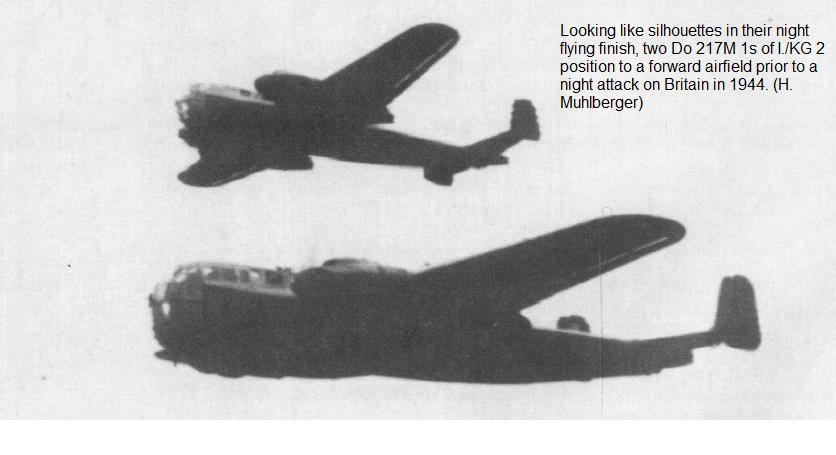

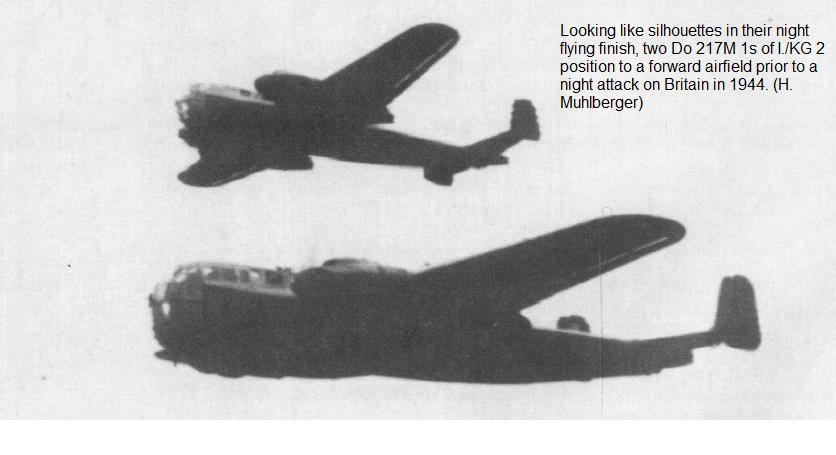

Peltz to train and equip his crews to a high standard. They were provided with a proliferation of radio navigation aids and many aircraft were fitted with radar night fighter warning systems and other advanced electronics. Further, in anticipation of British radio countermeasures. and to make up for the inexperience and lack of navigational expertise of many crews. Peltz had formed a specialist Pathfinder unit. I./KG 66. to mark both the target and turning points along the route with flares and other pyrotechnics. But none of these were enough, as was de-monstrated to good effect on the night of Monday. 27 March, when the attackers turned to the West Country. The target that night was the docks area of Bristol, then an important centre in the pre D-Day build-up of US forces in Britain. The attackers were to include Ju 188s of II./KG 2. Do 217s of III./KG 2 and Ju 88s of the following units: III./KG 6

and Stab/KG 30 from Bretigny II and III./KG 30 from

Paris/Orly; Stab/KG 54. II./KG 54 and I./KG 66 from

Laon/Athies; and I./KG 54 from Juvincourt. With the ex-

ception of III./KG 6. none were operating from their usual

home bases: in the face of Allied daylight air superiority

over France most bomber units were now based well back

from the Channel coast, making it necessary for them to

position to forward airfields to bomb-up and refuel before

each mission.

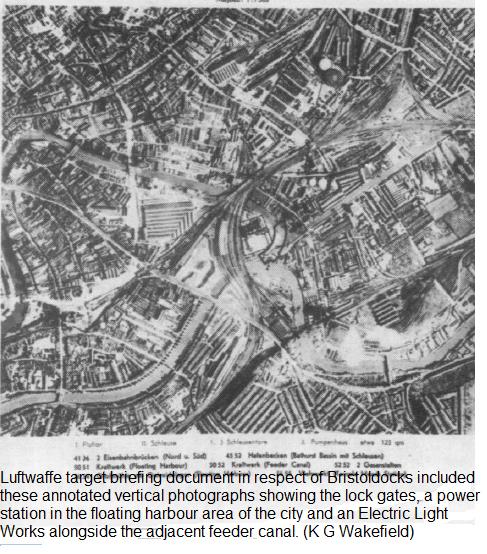

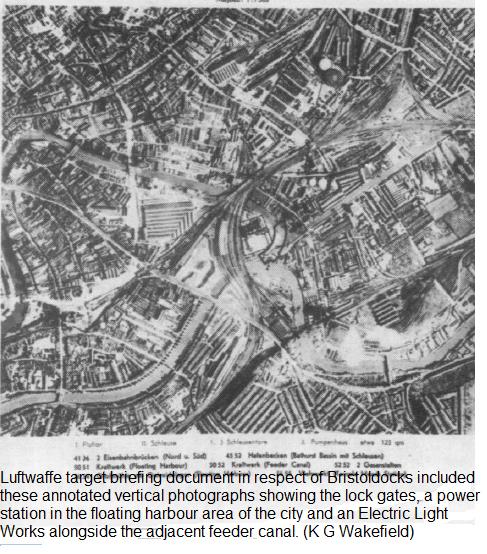

For the attack on Bristol the usual range of German visual

and radio navigation aids were to be employed. They in-

cluded powerful coastal radio beacons, used for track

keeping and direction finding (D/F). and the VHF beams

of Y-Verfahren and Knickebein. Among the latter. for

general use by the main force, the beam emanating from

Knickebein 10 was to be aligned over Bristol.

In a bid to saturate the defences the attack was to be con-

centrated in time, with all units bombing between midnight

and 12 minutes past the hour. To this end detailed plan-

ning, accurate navigation and precise timekeeping were

paramount, and crews were briefed accordingly. From their

various departure airfields they were to converge on

German-occupied Guernsey, which was to be marked by

a cone of six searchlights. The prescribed route then

crossed Lyme Bay. Somerset and the Bristol Channel to

an Initial Point at the mouth of the River Usk. which was to

be marked bv four red flares placed by the Pathfinders

of I./KG 66. From here the final approach to the target required a four-minute leg along the north bank of the River Severn to Beachley. near Chepstow, followed by a 90 degree turn to the

right for a short north-south run-in to Bristol. The Ju 88S aircraft of I./KG 66 were to mark the target with a cluster of white and yellow flares, but Pathfinder back-up - the renewal of flares over both the Initial Point and the target - was entrusted to four selected crews of II./KG 2. Units were allocated specific bombing heights, which varied between 11.000 and 14.500 feet,

and after bomb release all aircraft were to continue to a point eight miles south-south-west of Bath before turning to cross the Dorset coast near Bridport. Clearly there was no lack of

planning and in theory the attack should have been short, sharp and devastating. In practice, however, it began poorly and quickly degenerated into total disarray. Instead of a fast,

tightly knit bomber stream coming in over Lyme Bay. the 139 attackers fanned out over the English Channel and

crossed the coast well spread between Plymouth and Weymouth. Incredibly they then roamed the south and west of

England for about two hours. Nine overshot and penetrated to the Birmingham area, but most of the 112 enemy

aircraft plotted overland by Fighter Command remained in an area bounded by Lands End, Cardiff, Banbury,

Reading and Selsey Bill, where they widely scattered about 100 metric tonnes of bombs. Those that managed to

get anywhere near Bristol were first of all led astray by inaccurate marking of the Initial Point and then by target

marking flares dropped well to the west of the city. As a shambles il was a classic, with not a single bomb falling on

Bristol. Nor was London hit in a secondary attack that was no doubt intended to confuse the defenders. But what

confusion there was that night was all on the German side, as former Unteroffizier Matthias Josephs recalls.

Josephs was the radio operator in one of the 13 aircraft which failed to return that night. His Ju 188E-1 (coded

U5+EN) of 5./KG 2 was one of the four aircraft of this unit acting as back-up Pathfinders, and for this purpose was

carrying six LC 50 flares in addition to a bomb load of two AB 1000 incendiary canisters and four BC 50s. Having

positioned from Gilze Rijen to Vannes the previous day - at 300 feet to avoid being plotted by low- looking British

coastal radar stations - Josephs' aircraft took off on schedule and passed over the Guernsey searchlight cone as

planned. The Ju 188 crossed the coast on time near Lyme Regis, but then searchlights and flak made it necessary

for its pilot. Leutenant Werner Siebert, to take evasive action with a series of rapid and irregular changes of

heading and height. After a while course was resumed for the Initial Point, but shortly afterwards a cluster of target

marking white flares was seen to the left, instead of some 15- 20 miles to the right, as expected. From thereon

confusion reigned, with the crew arguing about their exact position and whether or not the flares were in the right

place. An attempt to check their position relative to the beam of Knickebein 10 was unsuccessful, so Siebert. who

had been forced to take more evasive action, decided to go ahead and bomb the flares in a north-south run.

However, unknown to the German crew a Beaufighter Mk VI (MM850) of No 68 Squadron, flown by Flying Officer

Russell with Flight Lieutenant Weir, radar opera- tor/navigator, was closing in on them. 'Pygmy 23*, as the Beau-

fighter was known to its controlling GCI Station at Exminster, had been on patrol since 2255 hours, but with nume.

rous enemy aircraft streaming in over the sector it was given a •freelance" role. With this approval to seek his own

'trade'. Flying Officer Russell headed for the best place to find an enemy aircraft - in the middle of a cone of search-

lights and flak. His first attempt proved unsuccessful, but a second cone of searchlights produced an AI radar

contact at 2.5 miles range. Four minutes later, after a stealthy approach under his AI operator's guidance. Russell

established visual contact with an enemy aircraft at a range of 1.000 feet. Closing in to 800 feet he identified it as a

Ju 88. and could see that it was dropping 'Duppel* reflective anti- radar strips (reported as 'window* by Russell,

using RAF terminology). As Kusseii was anout to open fire a burst of tracer from the Ju 188 passed over the night

fighter's starboard wing, but a short burst from the Beaufighter badly damaged the German bomber's tail and sent it

into a dive. The bombs were immediately jettisoned in a bid to escape but another burst of fire hit the Ju 188's port engine, which burst into flames. Escape was now out of the question and on Siebert's order the crew baled out. Their aircraft crashed shortly after midnight in a clover field at Coxley. near Wells. Somerset. Not far distant, near the Tin Bridge at Glastonbury, the five crew members - Siebert, Josephs and Unteroffizier Klaus Hoist (observer). Feldwebel Hermann Sagcl (gunner) and Gefreitcr Marcel Rozycki (bomb aimer) - landed in close proximity, with only the pilot injured. They were quickly rounded up by civilians, members of the Home Guard and the police and, as Matthias Josephs recalls, were taken to Glaston-

bury Police Station in jeeps from a nearby US Army camp. Some 28 years later Josephs returned to the place where he had landed and again visited the cell in which he had been

detained initially. And there, in happier circumstances, he again met his 'warder' former Police Constable 'Ginger' Harris. Josephs, who well remembers the events of that night, recalled: *I was due to go on leave after this flight, but instead I found myself a prisoner. We were all treated very fairly, but I must admit that when I first saw PC Harris he frightened me - he is a big man!"

Another German aircraft, a Ju 88A-4 (B3+UA) of Stab/KG 54. crashed a few miles away at Wed more, near Cheddar, but it appears that this was caused by an engine fire rather than by

British defensive action. Flown by Leutenant Wolfgang Fritz, the Ju 88 had positioned from Marx to Laon/Athies earlier in the day and departed for Bristol at 2130 hours, carrying two A8

1000 incendiary canisters. Its route from Laon/Athies was to Beauvais radio beacon, then via the Longuel beacon near Calais to Countances and on to Guernsey, from where the stan-

dard route was followed. After the attack the aircraft was to return to its North German base at Marx/Oldenburg. The weather was clear over the Channel but cloud covered the English coast, where search- light activity made it necessary for Leutnant Fritz to take evasive action. For an hour or more one engine had been giving cause for concern, but Fritz pressed on and three minutes before ETA the red flares of the Initial Point were seen, together with the target marking white flares. It should have been obvious that the two groups of flares were too close to be correctly placed, but Leutnant Fritz and his crew failed to appreciate this. They turned in towards the

white markers, which were actually well to the west of Bristol, and the bombs were released on a

southerly heading. A night fighter was then seen, and successfully avoided, but shortly afterwards the left

engine caught fire and the cabin tilled with smoke. Dr Wolfgang Fritz, as he now is, recalled: *I wasn't

particularly surprised at this because of the problems with excessively high oil pressure, that i had

experienced on the outward flight. But as the cabin filled with black smoke and I was unable to see any-

thing I ordered the crew to bale out. The emergency exit, the rear part of the canopy, was jettisoned and

we climbed out onto the wing and jumped. However, my radio operator was too anxious and opened his

parachute as he was getting out. with the result that it became entangled with the aircraft'. Radio operator

Unteroffizier Heinrich Schink was killed, but Fritz and the other two crew members. Obergefreiter Gunter

Baermann (observer) and Gefreiter Emil Schwenzer (gunner), landed safely to be taken prisoner. Fritz's

last operational flight was his sixth over England, the previous five having been attacks on London.

Before this he had flown six missions on the Italian front and in addition to the Iron Cross First and

Second Class had been awarded the Bronze Clasp.

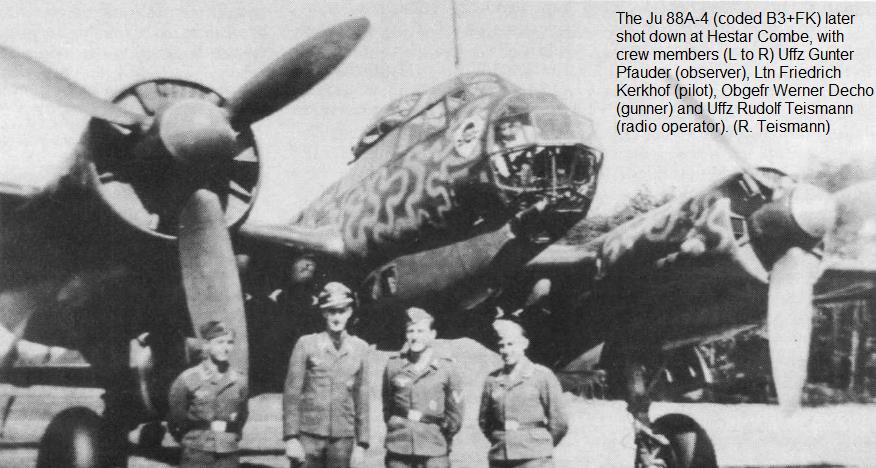

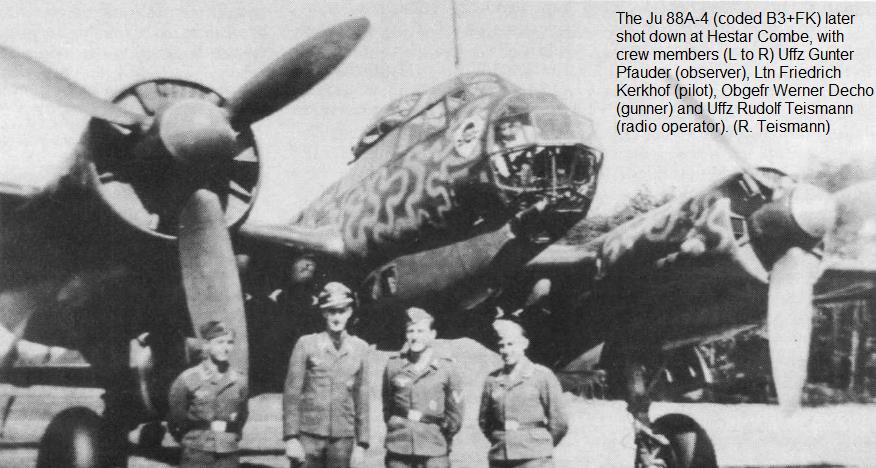

Another Ju 88A-4 of KG 54. the B3+FK of 2 Staffel. crashed at Hestar Combe, near Taunton, shot down

by Squadron Leader Ellis and Flight Lieutenant Craig in a Colerne-based Mosquito XVII of No 219

Squadron. The German pilot, Leutnant Friedrich Kerkhof, was killed, but the other three crew members

baled out with two of them. Unteroffizier Gunter Pfauder (observer) and Unteroffizier Rudolf Telsmann

(radio operator), each breaking a leg on landing. Obergefreiter Werner Decho (gunner) was taken

prisoner uninjured.

Quaintly named Isle Brewers, Somerset, was the crash site of another German bomber, this time a

Ju 88A-14 (B3+BL) of 3./KG 54 crewed by Oberfeldwebel Hans Brautigams (pilot), Obergefreiter Kurt

Chalon (observer), Unteroffizier Robert Belz (radio operator) and Obergefreiter Alfred Malezki (gunner).

Belz was killed, but the rest of the crew landed uninjured after bailing out. They were shot down by a Mosquito XVII of No 456 Squadron flown bv Wine Commander K Hampshire and Flying Officer T Condon, who had earlier shot down a Ju 88A-4 (3E+FT) of 9./KG 6 which crashed at Beer. Devon. The crew of this aircraft baled out over the sea and only one injured crew member survived. Another German airman, Unterroffizier Hahn. failed to return but in rather unusual circumstances; he abandoned his Ju 88 when it was damaged by anti aircraft fire but lost his life in the process. His parachute- less body was found at Chelborough. Dorset, but his aircraft with three other crew members returned safely to France. The one thing favouring some of the attacking aircraft - notably the Ju 88S and Ju 188 - was their high speed, and but for this German losses would have been much higher. Violent evasive action also paid divi-

dends, and both factors were commented on by

the crews of four Mosquito XVIIs of No 125

Squadron. Scrambled from Hum all four were

involved in the pursuit of the enemy aircraft, but

landed back at Odiham with nothing to report but

frustration.

The performance of the Beaufighter - which was

appreciably slower than the Mosquito - also

drew comment from the Canadians of No 406

Squadron. Ten aircraft of this squadron were

scrambled from Exeter as soon as hostile plots

were reported, but despite the performance

limitations of their aircraft they scored two victories.

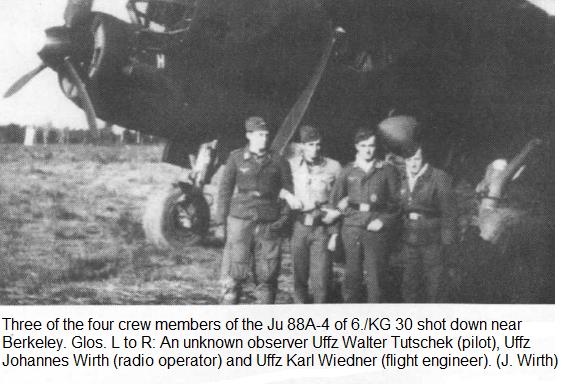

The first, which crashed at Clapton. near Berkeley.

Gloucestershire, was a Ju 88A-4 (4D+EP) of

6./KG 30 shot down by Flight Lieutenant H D

McNabb and Pilot Officer J L N Hall (an English-

man serving with the Canadian squadron) in

KW981. a Beaufighter Mk VIF

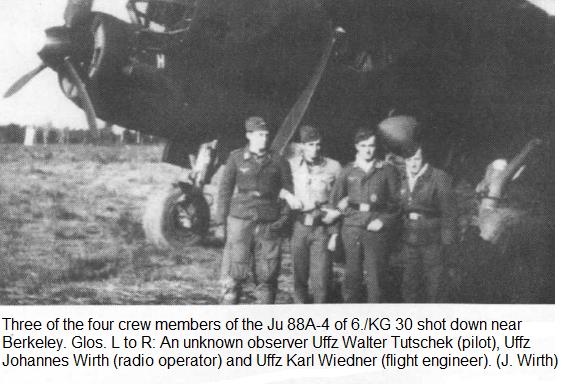

The German pilot, Unteroffizier Walter Tutschek.

and his crew - Obergefreiter Otto Bauch

(observer). Unteroffizier Hans Wirth (radio opera-

tor) and Unteroffizier Karl Weidner (gunner) -

baled out successfully, only the last named being

injured. Typically, all were in their early twenties -

one was 21 years old, another was 22, the oldest was 23 and the fourth, the pilot and aircraft commander, was 20.

No 406 Squadron's second victory went to Pilot Officers R L Green and A W Hillyer (another Englishman) in Beaufighter VIF KW1I9; they shot down a Ju 188 some 20 miles south of Plymouth and this could well have been an aircraft reported missing by 5./KG 2. The other aircraft which failed to return that night were a Ju 88S of I./KG 66. a Do 217 of 7./KG 2 and two Ju 88s of 6./KG 6. Over their own territory eight Ju 88s of 2./KG 54 crashed near Juvincourt and an RAF intruder shot down a Ju 88 of 7./KG 30 near Cherbourg. In all, the attack cost the Germans 13 aircraft, or nearly 10 per cent of the number dispatched. The next day the German official war communique claimed '....a heavy raid on Bristol, with violent explosions, extensive havoc and vast conflagrations'. But in fact, as pre- viously stated, no bombs what-soever fell on Bristol and so widely scattered was the bombing that the British Ministry of

Home Security was quite unable to deduce the enemy's objective. Only with the grossly inaccurate German news broadcasts was the intended target discovered. In truth, it really was a raid that never was.

AVIATION NEWS - MARCH 1991